5. Design by Contract

5.1 Correctness

Design by contract (DbC), also known as contract programming, programming by contract and design-by-contract programming, is an approach for designing software. It prescribes that software designers should define formal, precise and verifiable interface specifications for software components, which extend the ordinary definition of abstract data types with preconditions, postconditions and invariants. These specifications are referred to as "contracts", in accordance with a conceptual metaphor with the conditions and obligations of business contracts.

Before we will proceed to contracts, we need to understand why we need to learn this theme, and the first term we need to understand is "system correctness".

// Example 1

const doSomething = (x) => {

return x / 2;

}

// Example 2

// { x = 5 } x = x ˆ 2 { x > 0 } => the weakest postcondition

// Example 3

// { x = 5 } x = x ˆ 2 { x = 25 } => the strongest postcondition

This function by itself is neither correct nor incorrect, correctness can be applied when we talk about expected results. This function is correct if we say that "Returned value is half the size of the argument", but it is not correct if we say that "Returned value should be positive" because there are no guarantees that the function will not receive a negative number as the argument.

This example makes it clear that correctness can be applied to the specification, but not to the function code.

The next part we need to review is a Hoare triple from examples two and three. The first triple is correct as before the operation x ^ 2 precondition is met and x is equal to 5, then after the operation postcondition (x is greater than 0) also will be met (subject to correct implementation of integer arithmetic). In this example postcondition is not the strongest one, the strongest possible postcondition for this precondition is {x = 25} and the weakest one is {x > 0}. We always can create a new triple from existing one making precondition and postcondition weaker or stronger.

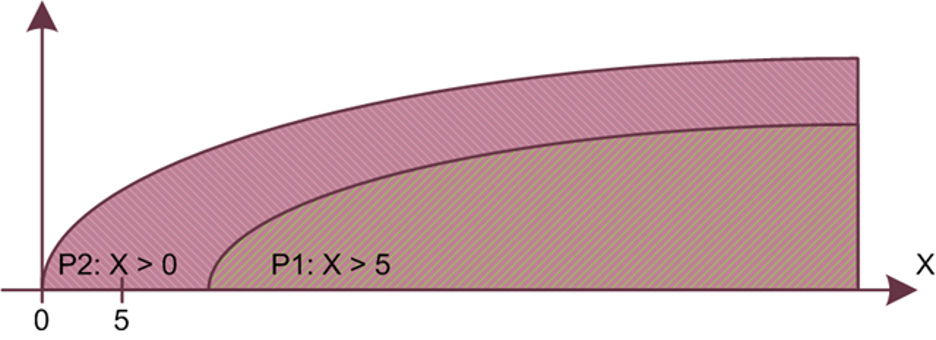

Figure 5.1 - x > 5 is stronger than x > 0

The concept of "stronger" and "weaker" came from logic. It is said that the condition P1 is stronger than P2, and P2 is weaker than P1 if the fulfillment of P1 implies the fulfillment of P2, but they are not equivalent. For example, x > 5 (P1) is stronger than x > 0 (P2), since if P1 is fulfilled, P2 is fulfilled as well (after all, if x is greater than 5, then, naturally, x is greater than 0), and they are not equivalent.

class Stack<T> {

private count = 0;

private maxAmount = 15;

public push(e: T) {

console.assert(this.count < this.maxAmount, 'Stack not overflown');

const previousCount = this.count;

// method implementation

console.assert(this.count === previousCount + 1, 'One more item');

}

public pop(): T {

console.assert(this.count !== 0, 'Stack is empty');

// method implementation

console.assert(result !== null, 'Result is not null');

console.assert(this.count === previousCount - 1, 'One less item');

return result;

}

}

Each function has strict semantic properties that reflect what the function does, regardless of how it does it.

In this case, preconditions define properties that must be met every time before function is executed, and postconditions - those properties that must be met after its execution.

The precondition binds the calling code: the conditions are defined under which the program call by the client is legitimate (for example, x > 0 for the Sqrt function or count ! = 0 for the Pop function of the Stack class). In this case, the client's obligations benefit the provider class, since the class performing the operation does not need to worry about what to do if a precondition is violated: return a default value or error code, throw an exception, save information about the error to the I/O stream, or interrupt the program execution.

The postcondition binds the class: the conditions that must be met upon completion of the operation are determined (the Stack class must provide an increase in the number of elements by 1 after the push function is executed). Here, the client's benefit (the result of performing the function) turns into the supplier's obligations (he can no longer fail to fulfill his obligations, since they are spelled out in the contract).

5.2 Preconditions and Postconditions for Inheritance

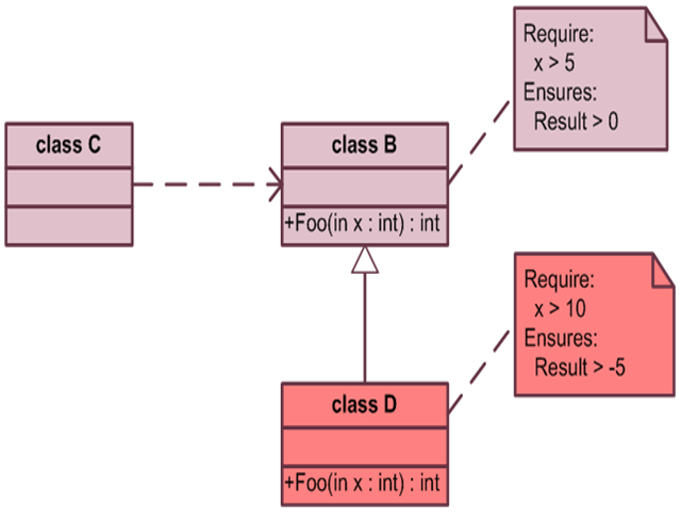

Let us review an example from Figure 5.2 where we have C class which contains link to a B class. Due to dynamic linking D class (or any other B subclass) can be used instead of B class after the start of program execution.

Figure 5.2 - B – C – D classes relations

class B {

public foo(x: number): number {

console.assert(x > 5, 'x > 5');

//method implementation

console.assert(result, 'result > 0');

return result;

}

}

class C {

private b: B;

public bar(x: number) {

if (x > 5) {

const result = this.b.foo(x);

console.assert(result > 0, 'result > 0');

}

}

}

B class has a public foo function with a precondition of x > 5 (pre_b) and a postcondition result > 0 (post_b). By checking the precondition, class C fulfills its part of the contract and can expect class B (or one of its subclasses) to fulfill the contract. According to the Liskov substitution principle, the behavior of the given code fragment should not change if we substitute any B subclass.

Let us assume that the function foo in class D starts to require more (contains a stronger precondition like x > 10), and guarantees less (contains a weaker postcondition like x > -5)

In this case, although the client of class B fulfills its part of the contract and provides an input value to the function foo that satisfies the precondition, it may not get the expected result. Strengthening the precondition means that the data correct for the base class will become incorrect for its subclass (in our example, it can be the value x equal to 6), and weakening the postcondition means that the result that the client of the base class expects may not be returned by the subclass (in our example, this could be the result of the function Foo equal to -1).

Hence, we can conclude that when overriding methods, the precondition can be replaced only by an equal or weaker one (require less), and a postcondition - only equal to it or stronger (guarantees more). The new version of the method should not reject calls allowed in the original, and should, at a minimum, provide guarantees equivalent to those of the original version. It is free, although not obligated, to allow more calls or provide stronger guarantees.

5.3 Covariance and Contravariance

Based on the previous example, we can come to terms such as covariant and contravariant, when replacing the base class with its subclass, the input values for its methods must be contravariant, that is, the precondition must be the same or weaker, and the output values must be covariant, that is, the same or stronger. Consider the following example for better understanding:

class Locality {}

class City extends Locality {}

class NewYork extends City {}

function covariance(city: City): void {}

covariance(new Locality()); // error... does not support supertype

covariance(new City()); // ok support exact type

covariance(new NewYork()); // ok support subtype

function contravariance(city: City): void {}

contravariance(new Locality()); // ok support supertype

contravariance(new City()); // ok support exact type

contravariance(new NewYork()); // error... does not support subtype

We have inheritance structure built of three classes, Locality as a base class and City and NewYork as more specific classes. Function with name covariance accepts City instances as an argument, but it also can accept NewYork instances as the more specific subclass and at the same time it can not accept City superclass as the argument – Locality because covariance will be violated in such case. Everything is vice versa for the contravariance function – it can accept City and its supertype as the argument but cannot accept City subclass.

Let us look on another example, with a more detailed implementation, to understand how contravariance works on input values:

class Price {}

class Destination {}

class USADestination extends Destination {}

class TexasDestination extends USADestination {}

class ShippingCalculator {

public getRate(destination: USADestination): Price { return new Price() }

}

class InternationalShippingCalculator extends ShippingCalculator {

// ok - contravariance on input value

public getRate(destination: Destination): Price { return new Price() }

}

class TexasShippingCalculator extends ShippingCalculator {

// wrong - covariance on input value

public getRate(destination: TexasDestination): Price { return new Price() }

}

In this example, we also have an inheritance hierarchy of three classes, the base Destination, its USADestination subclass and the even more specific TexasDestionation class. If we want to create a ShippingCalculator class that will accept USADestination as input and return the Price to us, and then create its InternationalShippingCalculator subclass which will already accept any Destination as input, then this will be correct since the contravariance of the input values is observed, and we can replace the ShippingCalculator with InternationalShippingCalculator, and it will work. But if after that we want to extend the functionality of the ShippingCalculator by creating its TexasShippingCalculator subclass which will only accept TexasDestionation as input, then in this case we can already say that the contravariance is not observed, since the input value is more specific, and in this case we cannot replace the ShippingCalculator on TexasShippingCalculator while keeping the system working.

Based on the next example we will find out how to meet contravariance for the output values:

class Animal {

public feed(food): void { console.log('yumm!') }

public walk(): void { throw new Error('Not implemented') }

}

class Snake extends Animal {

public crawl(): void { console.log('crawling') }

}

class Wolf extends Animal {

public walk(): void { console.log('walking') }

}

class CanisLupus extends Wolf {}

class ZooCage {

public getContent(): Wolf { return new Wolf() }

}

class CanisLupusCage extends ZooCage {

// ok - returns subtype

public getContent(): CanisLupus { return new CanisLupus() }

}

class Terrarium extends ZooCage {

// wrong - returns supertype

public getContent(): Animal { return new Snake() }

}

We have the base Animal class and its three subclasses, while the Snake and Wolf classes are its direct subclasses, and the CanisLupus class is a Wolf subclass. If we want to create a ZooCage class that will return the contents of the cage and the expected output value will be the Wolf class, then to maintain covariance in the CanisLupusCage class, we need to return the Wolf or CanisLupus class. If we create a Terrarium class with an output value of the Animal class, then the covariance will not be met, since the Animal class is a superclass of the Wolf class.