3. Mixins

3.1 Sharing Role Behavior with Mixins

Mixins is another OOD tool, inheritance is not the only way to share a behavior, every problem which we solve using inheritance also can be solved using other tools, and one of such tools are mixins. But each tool has its pros and cons so let us look on what mixins can give us and what the price we must pay to use them.

3.2 Understanding Roles

Sometimes you need to share some behavior between non-related objects, such case is a direct opposite to inheritance hierarchy (IS-A relation). It is rather a role, which object can play on some state of its lifecycle. Let us review some basic example below:

const sayMixin = {

say(phrase) {

alert(phrase);

}

};

const sayHiMixin = {

__proto__: sayMixin,

sayHi() {

super.say(`Hello ${this.name}`);

},

sayBye() {

super.say(`Bye ${this.name}`);

}

};

class User {

constructor(public name) {}

}

We have sayMixin with say method which prints given phrase on the screen, we also have its extended version – sayHiMixin. When you need to use mixin functionality on some object, you can just add it to the object's prototype, and this will give us the possibility to use mixins methods on this object.

Object.assign(

User.prototype,

sayHiMixin

);

new User('Dave').sayHi();

But such approach has some consequences, prototypes functionality is not the most convenient in usage, apart from that, Object.assign() only makes a shallow copy, so you can use existing JavaScript libraries to make mixins usage easier.

3.3 Writing the Concrete Code

To better understand how mixins work and what they can give us we will go back to bicycles example. Let us look on the case when we need to make our bicycles schedulable, this functionality will give as an opportunity to schedule a single bicycle on a specific period. We also need to add leadDays property which will store number of days required to prepare the bicycle.

class Schedule {

isScheduled(schedulable, starting, ending) {

console.log(`Checking if ${schedulable.constructor.name}`

+ `is available on ${starting} - ${ending}`);

//do the checks

return true;

}

}

class Bicycle {

leadDays = 1;

constructor(parts, schedule = new Schedule()) {

this.schedule = schedule;

// ...

}

isSchedulable(starting, ending) {

const withLeadTime = starting - this.leadDays;

return this.schedule.isScheduled(this, withLeadTime, ending);

}

}

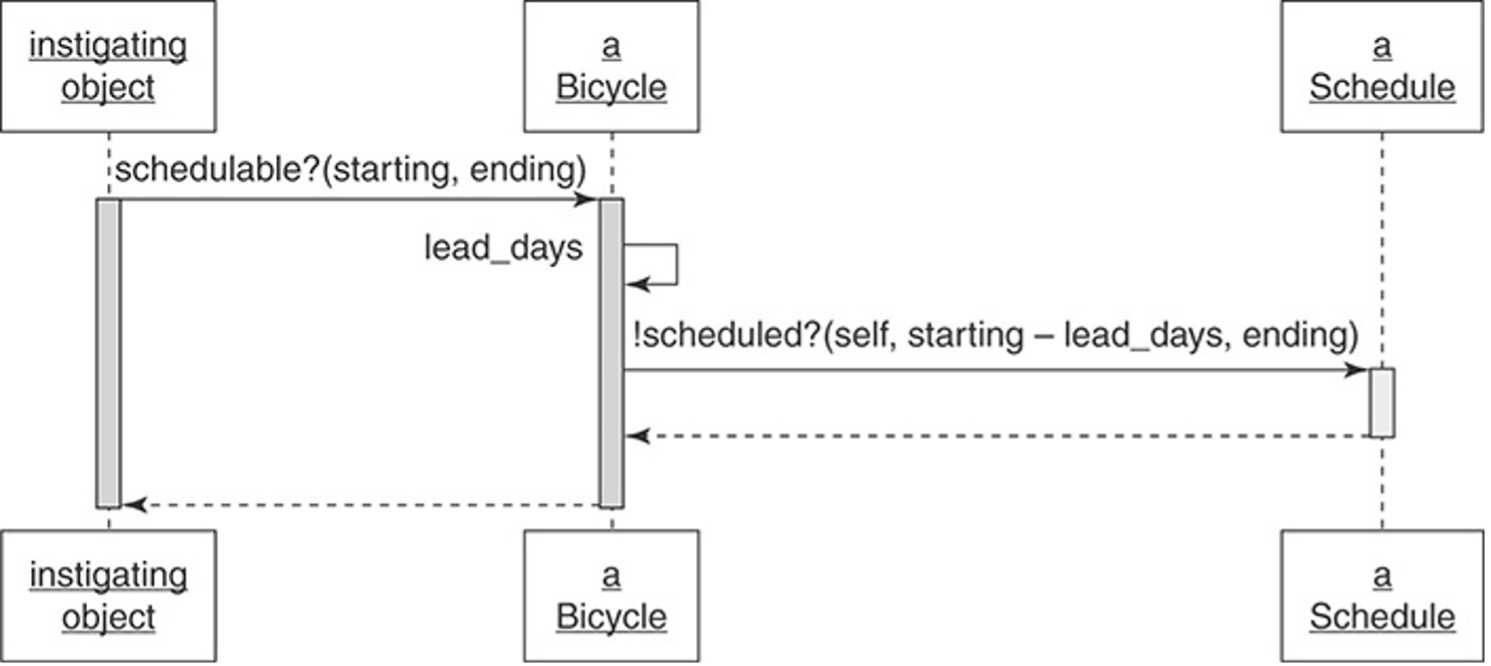

Figure 3.1 - Bicycle classes know if they are schedulable

Based on the result above and UML-diagram from Figure 3.1 we can say that major part of logic is stored in Schedule class, this class is used in isSchedulable method, it needs two dates, one for the start and one for the end of booking, Schedule instance receives start date with subtracted leadDays, so we will always have enough time to prepare the bicycle for a trip. Now we can schedule a bicycle, but we also have other classes like Mechanic and Driver and each of them has its own leadDays value. Extracting common logic, we can create Schedulable duck type.

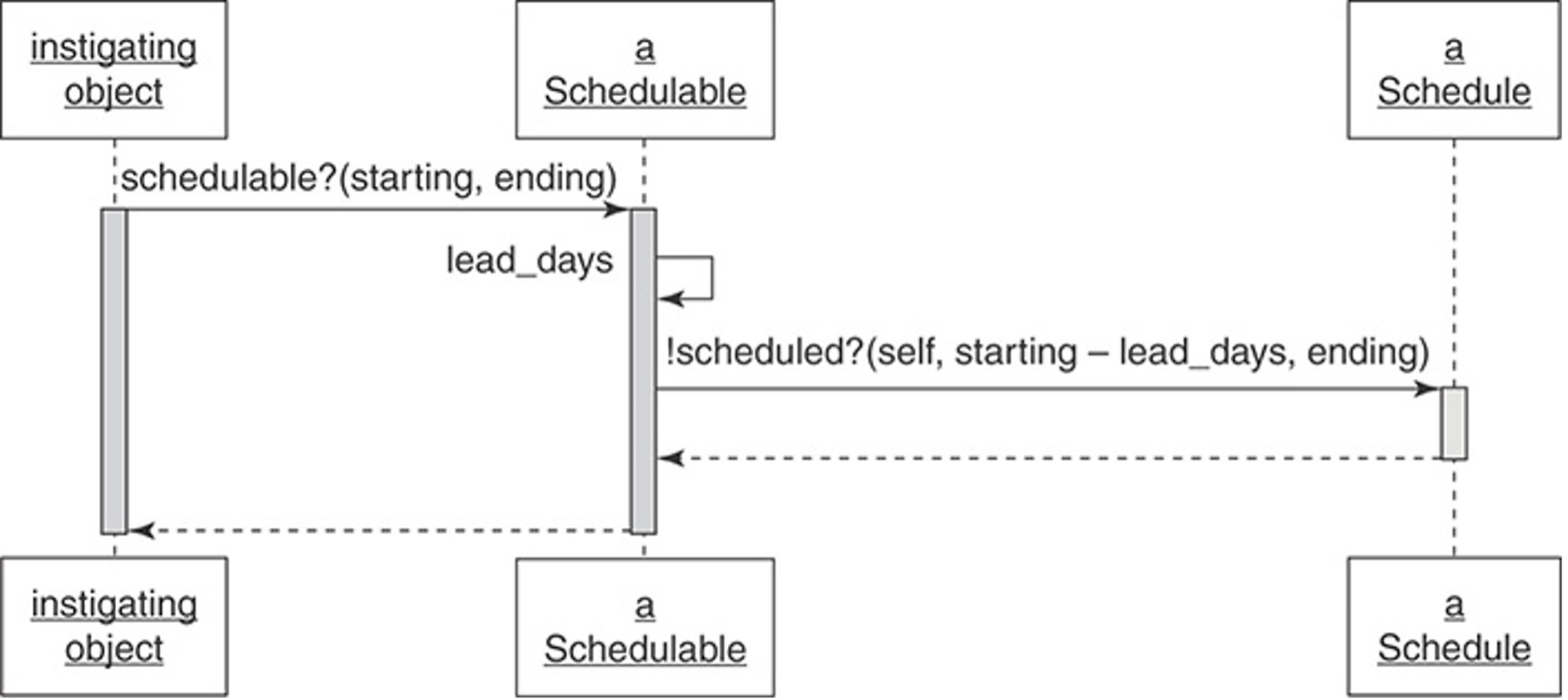

Figure 3.2 - Schedulable duck type

Let us review UML-diagram from Figure 3.2, we have new Schedulable instance, but relation between Bicycle and Schedulable is not IS-A, because Bicycle should not be schedulable under normal conditions. This duck type rather describes Bicycle specific behavior when it is required to be scheduled for the trip, or under specific conditions in other words. Other parts of our system should not even know that Bicycle is schedulable, these classes relations will be better to describe as BEHAVES-AS.

const SchedulableMixin = (superclass) => class extends superclass {

private _schedule: Schedule;

protected leadDays = 0;

set schedule(schedule) {

this._schedule = schedule;

}

get schedule() {

return this._schedule || new Schedule();

}

isSchedulable(starting, ending) {

const withLeadDays = starting - this.leadDays;

return this.schedule.isScheduled(this, withLeadDays, ending);

}

}

class Bicycle extends SchedulableMixin(Object) {

protected leadDays = 1;

}

class Vehicle extends SchedulableMixin(Object) {

protected leadDays = 3;

}

class Mechanic extends SchedulableMixin(Object) {

protected leadDays = 4;

}

We have extracted common logic to SchedulableMixin with isSchedulable method, and now we can easily mix it to any class in our hierarchy, either Bicycle, Mechanic or Driver, so we will have schedulable behavior when we only need it. In this case decorators could be used as an alternative solution, you may know about them from TypeScript, and they solve this problem in as similar manner, so mixins are not the only solution to add a behavior. The only consequence in Schedulable mixin is that we need to store leadDays property in a target class, so it can be used in mixin.

3.4 Mixins: Writing Inheritable Code

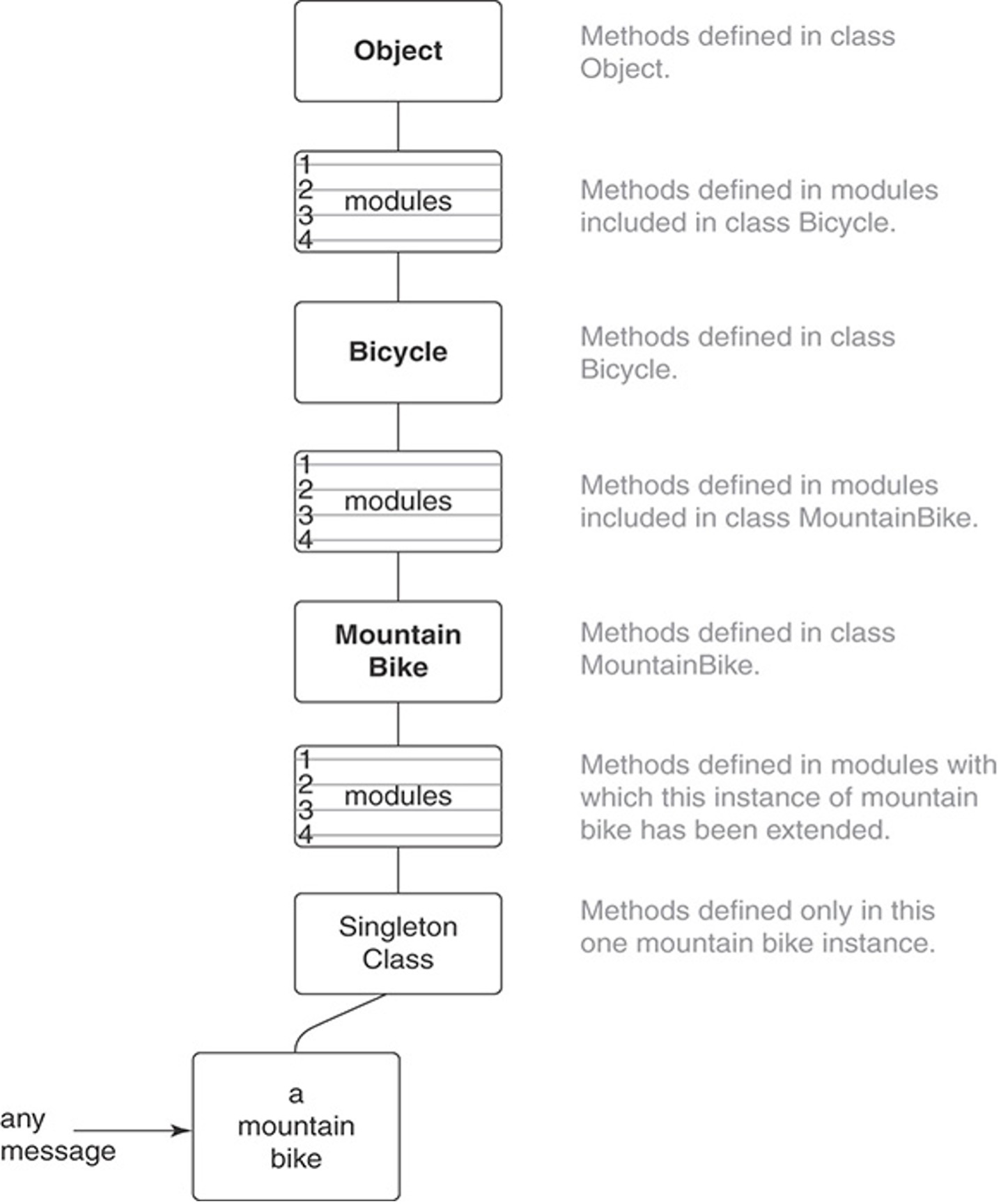

To better understand which consequences mixins have in general let us review the scheme from Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3 - Mixins call stack

Taking a closer look at this scheme we can notice that mixins added additional levels to the call stack, this makes understanding and debugging of the application less obvious, so you need to keep this in mind and use mixins only when they are really needed.

- Recognize the Antipatterns. There are two antipatterns which may indicate that you can gain a benefit from inheritance. First of them is using variables with a type/category to determine a type of object and send it a message. The second is usage of direct object type checking or switch-case operator – then you rather missed a duck type. Duck types may have not only common interface but also common behavior, which is recommended to extract to mixins.

- Insist on the Abstraction. All the code in an abstract superclass which should be used in every subclass, superclasses should not contain a code which is only applied for some subclasses. This limitation is also applicable to mixins, all the mixin functionality should be used in every place where it is mixed in. If you cannot identify an abstraction, then probably it is not existing, and inheritance cannot be applied to solve this problem.

- Honor the Contract. Subclasses must honor the contract, so they can be easily replaced with superclasses without any change in a system behavior. This means that they need to answer on the same messages receiving the same input data and returning the same result data. Thereby they cannot do something which will force a client code to check them for a type to understand what to wait from them. Subclasses which do not honor the contract cannot work synchronously thus making all the inheritance hierarchy unpredictable. This also violates Liskov Substitution Principle which you will learn about in the lecture about SOLID.

- Preemptively Decouple Classes. Try to avoid super method call, use template method pattern and so-called hooks instead, they give subclass a possibility to specify the common algorithm which is controlled by superclass. Remember that it is not a "silver bullet" and do not follow this approach blindly.

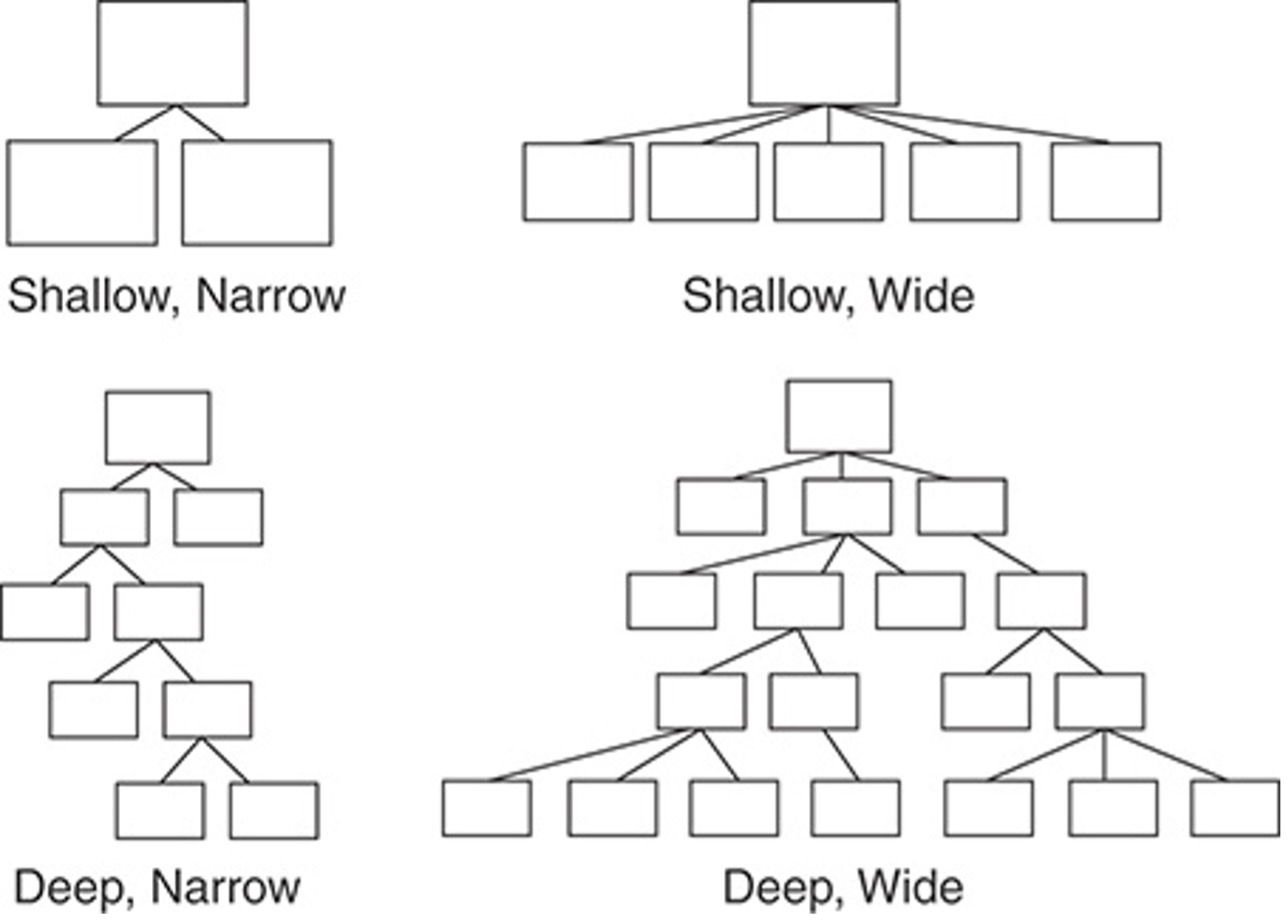

- Create Shallow Hierarchies (Figure 3.4). Try to create as compact hierarchies as it is possible. Shallow hierarchies are easy to understand, shallow and wide are slightly more difficult, but they still are easy to understand. Deep and narrow hierarchies tend to become wider and much difficult to understand and maintain. You should avoid deep and wide hierarchies, they create a long path to target method or property which is missing in a target class. Such hierarchies are difficult to maintain, and they create a high risk of application failure.

Figure 3.4 - Hierarchies come in different shapes