4. Behavioral Design Patterns

Behavioral design patterns are related to algorithms and the assignment of responsibilities between objects. They can be based on both – inheritance and composition.

4.1 Template Method

Template Method is a behavioral design pattern that defines the skeleton of an algorithm in the superclass but allows subclasses to override specific steps of the algorithm without changing its structure.

4.1.1 Template Method structure

The Template Method pattern suggests you break down an algorithm into a series of steps, turn these steps into methods, and put a series of calls to these methods inside a single template method. The steps may either be abstract, or have some default implementation. To use the algorithm, the client is supposed to provide its own subclass, implement all abstract steps, and override some optional ones if needed (but not the template method itself).

There are three types of steps:

- abstract steps must be implemented by every subclass

- optional steps already have default implementation, but can be overridden if needed

- hooks are optional steps with an empty body. A template method would work even if a hook is not overridden. Usually, hooks are placed before and after crucial steps of algorithms, providing subclasses with additional extension points for an algorithm.

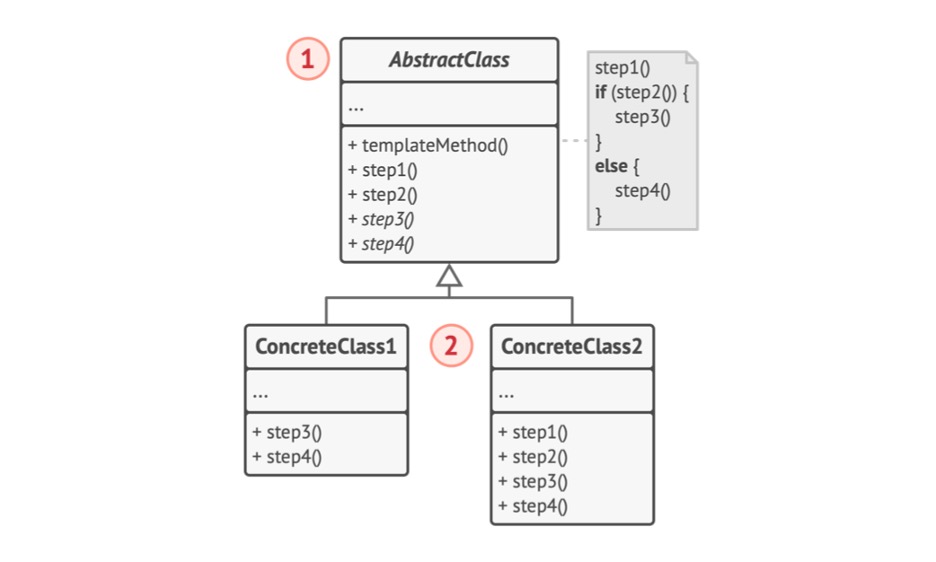

Figure 4.1 - Template Method

- The

AbstractClassdeclares methods that act as steps of an algorithm, as well as the actual template method which calls these methods in a specific order. The steps may either be declared abstract or have some default implementation. ConcreteClasses can override all the steps, but not the template method itself.

boilWater();

brew();

pourInCup()

addCondiments();

4.1.2 Template Method example

abstract class Builder {

// Template method

public build() {

this.test();

this.lint();

this.assemble();

this.deploy();

}

abstract test();

abstract lint();

abstract assemble();

abstract deploy();

}

class AndroidBuilder extends Builder {

public test() { return 'Running android tests'; }

public lint() { return 'Linting android code'; }

public assemble() { return 'Assembling android build'; }

public deploy() { return 'Deploying android build to server'; }

}

class IosBuilder extends Builder {

public test() { return 'Running ios tests'; }

public lint() { return 'Linting ios code'; }

public assemble() { return 'Assembling ios build'; }

public deploy() { return 'Deploying ios build to server'; }

}

const androidBuilder = new AndroidBuilder();

androidBuilder.build();

// Running android tests

// Linting android code

// Assembling android build

// Deploying android build to server

const iosBuilder = new IosBuilder();

androidBuilder.build();

// Running ios tests

// Linting ios code

// Assembling ios build

// Deploying ios build to server

4.1.3 When to apply, pros and cons

- to let clients extend only particular steps of an algorithm, but not the whole algorithm or its structure. The Template Method lets you turn a monolithic algorithm into a series of individual steps which can be easily extended by subclasses while keeping intact the structure defined in a superclass

- when you have several classes that contain almost identical algorithms with some minor differences. As a result, you might need to modify all classes when the algorithm changes. When you turn such an algorithm into a template method, you can also move the steps with similar implementations into a superclass, eliminating code duplication. Code that varies between subclasses can remain in subclasses

Pros

- letting clients override only certain parts of a large algorithm, making them less affected by changes that happen to other parts of the algorithm

- move the duplicate code into a superclass

Cons

- some clients may be limited by the provided skeleton of an algorithm

- you might violate the Liskov Substitution Principle by suppressing a default step implementation via a subclass

- template methods tend to be harder to maintain the more steps they have

4.2 Strategy

Strategy is a behavioral design pattern that lets you define a family of algorithms, put each of them into a separate class, and make their objects interchangeable. Allows switching between algorithms or strategies depending on situation.

4.2.1 Strategy structure

The Strategy pattern suggests you take a class that does something specific in a lot of diverse ways and extract all these algorithms into separate classes called strategies. The original class, called context, must have a field for storing a reference to one of the strategies. The context delegates the work to a linked strategy object instead of executing it on its own.

The context is not responsible for selecting an appropriate algorithm for the job. Instead, the client passes the desired strategy to the context. In fact, the context does not know much about strategies. It works with all strategies through the same generic interface, which only exposes a single method for triggering the algorithm encapsulated within the selected strategy. This way the context becomes independent of concrete strategies, so you can add new algorithms or modify existing ones without changing the code of the context or other strategies.

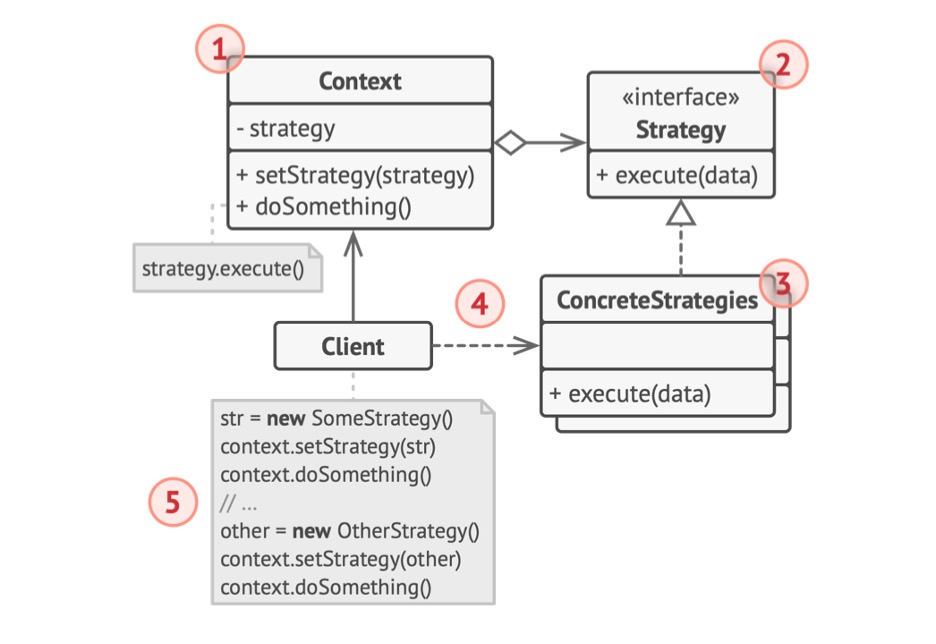

Figure 4.2 - Strategy

- The

Contextkeeps a reference to one of the concrete strategies and communicates with this object only via the strategy interface. - The

Strategyinterface is unified for all concrete strategies. It declares a method the context uses to execute a strategy. ConcreteStrategiesimplement different variations of an algorithm the context uses.- The context calls the execution method on the linked strategy object each time it needs to run the algorithm. The context does not know what type of strategy it works with or how the algorithm is executed.

- The

Clientcreates a specific strategy object and passes it to the context. The context exposes a setter which lets clients replace the strategy associated with the context at runtime.

4.2.2 Strategy example

// The strategy interface declares operations common

// to all supported versions of some algorithm.

interface Strategy {

execute(a: number, b: number): number;

}

// Concrete strategies implement the algorithm while following

// the base strategy interface. The interface makes them

// interchangable in the context.

class ConcreteStrategyAdd implements Strategy {

execute(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

}

class ConcreteStrategySubstract implements Strategy {

execute(a, b) {

return a - b;

}

}

class ConcreteStrategyMultiply implements Strategy {

execute(a, b) {

return a * b;

}

}

We have common interface and 3 concrete classes implementing this interface. The Context in not aware of what specific strategy he works with. Context knows that it can send the execution message. Thus, the client decides when and which strategy should be used. It can switch them on the fly, getting different behavior, without changing the interface.

// The context defines the interface of interest to clients.

class Context {

private strategy: Strategy;

setStrategy(s: Strategy) {

this.strategy = s;

}

// The context delegates some work to the strategy object

// instead of implementing multiple versions of the

// algorithm on its own.

executeStrategy(a: number, b: number) {

return this.strategy.execute(a, b);

}

}

let ctx = new Context();

ctx.setStrategy(new ConcreteStrategyAdd());

ctx.executeStrategy(5, 2); // 7

4.2.3 When to apply, pros and cons

- when you want to use different variants of an algorithm within an object and be able to switch from one algorithm to another during runtime. The Strategy pattern lets you indirectly alter the object's behavior at runtime by associating it with different sub-objects which can perform specific sub-tasks in diverse ways

- when you have a lot of similar classes that only differ in the way they execute some behavior. The Strategy pattern lets you extract the varying behavior into a separate class hierarchy and combine the original classes into one, thereby reducing duplicate code

- to isolate the business logic of a class from the implementation details of algorithms that may not be as important in the context of that logic. The Strategy pattern lets you isolate the code, internal data, and dependencies of various algorithms from the rest of the code. Various clients get a simple interface to execute the algorithms and switch them at runtime

- when your class has a massive conditional operator that switches between different variants of the same algorithm

Pros

- swapping algorithms used inside an object at runtime

- isolating the implementation details of an algorithm from the code that uses it

- replacing inheritance with composition

- introducing new strategies without having to change the context

Cons

- if you have only a couple of algorithms, and they rarely change, there is no real reason to overcomplicate the program with new classes and interfaces that come along with the pattern

- clients must be aware of the differences between strategies to be able to select a proper one

4.3 Visitor

Visitor is a behavioral design pattern that lets you separate algorithms from the objects on which they operate.

4.3.1 Visitor structure

Imagine that your team develops an app which works with geographic information structured as one colossal graph. Each node of the graph may represent a complex entity such as a city, but also more granular things like industries, sightseeing areas, etc. The nodes are connected with others if there is a relation between the real objects that they represent. Under the hood, each node type is represented by its own class, while each specific node is an object.

At some point, you got a task to implement exporting the graph into XML format. At first, the job seemed straightforward. You planned to add an export method to each node class and then leverage recursion to go over each node of the graph, executing the export method. The solution was simple and elegant: thanks to polymorphism, you were not coupling the code which called the export method to concrete classes of nodes. The Visitor pattern suggests you put the new behavior into a separate class called visitor, instead of trying to integrate it into existing classes. The original object that has to perform the behavior is now passed to one of the visitor's methods as an argument, providing the method access to all necessary data contained within the object.

Now, what if that behavior can be executed over objects of different classes? For example, in our case with XML export, the actual implementation will probably be a little different across various node classes. Thus, the visitor class may define not one, but a set of methods, each of which could take arguments of different types.

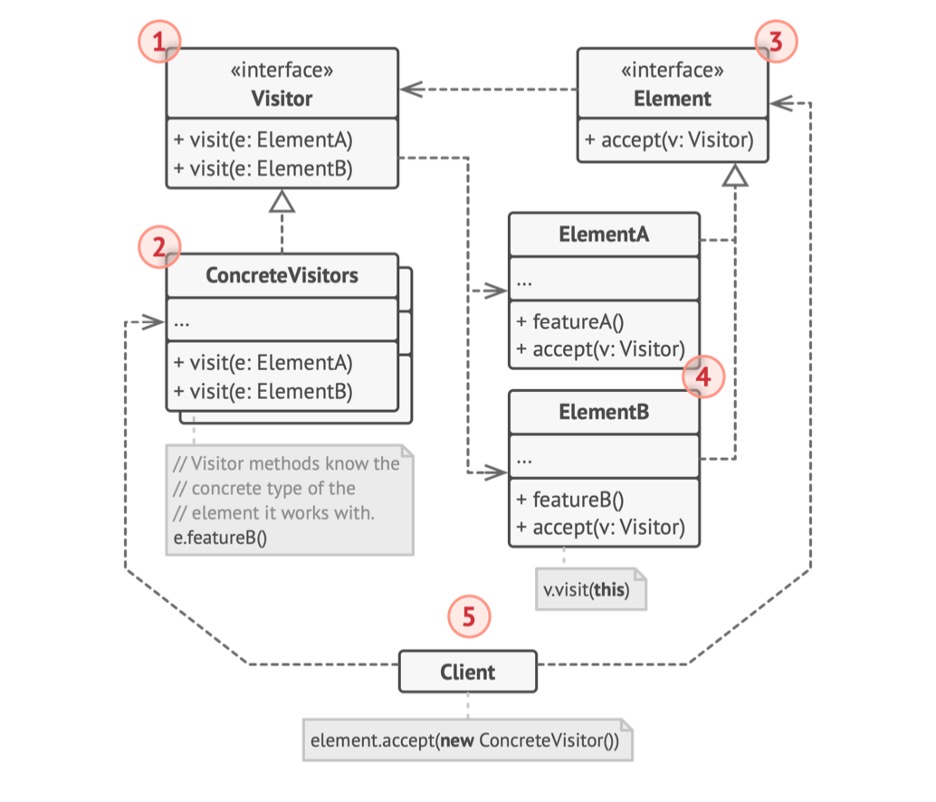

Figure 4.3 - Visitor

- The

Visitorinterface declares a set of visiting methods that can take concrete elements of an object structure as arguments. These methods may have the same names if the program is written in a language that supports overloading, but the type of their parameters must be different. - Each

ConcreteVisitorimplements several versions of the same behaviors, tailored for different concrete element classes. - The Element interface declares a method for "accepting" visitors. This method should have one parameter declared with the type of the visitor interface.

- Each

ConcreteElementmust implement the acceptance method. The purpose of this method is to redirect the call to the proper visitor's method corresponding to the current element class. Be aware that even if a base element class implements this method, all subclasses must still override this method in their own classes and call the appropriate method on the visitor object. - The

Clientusually represents a collection or some other complex object (for example, a Composite tree). Usually, clients are not aware of all the concrete element classes because they work with objects from that collection via some abstract interface.

4.3.2 Visitor example

The element interface declares an accept method that takes the base visitor interface as an argument. Each concrete element class must implement the accept method in such a way that it calls the visitor's method that corresponds to the element's class.

// The component interface declares an 'accept' method that

// takes the base visitor interface as an argument.

interface Shape {

move(x, y);

draw();

accept(v: Visitor);

}

// Each concrete component class must implement the 'accept' method

class Dot implements Shape {

accept(v: Visitor) { v.visitDot(this); }

move(x, y) {}

draw() {}

}

class Circle implements Shape {

accept(v: Visitor) { v.visitCircle(this); }

move(x, y) {}

draw() {}

}

class Rectangle implements Shape {

accept(v: Visitor) { v.visitRectangle(this); }

move(x, y) {}

draw() {}

}

The Visitor interface declares a set of visiting methods that correspond to element classes. The signature of a visiting method lets the visitor identify the exact class of the element that it's dealing with.

// The Visitor interface declares a set of visiting methods that

// correspond to component classes.

interface Visitor {

visitDot(d: Dot);

visitCircle(c: Circle);

visitRectangle(r: Rectangle);

}

class JSONExportVisitor implements Visitor {

visitDot(d: Dot) {

// Export the dot's ID and coordinates.

}

visitCircle(d: Circle) {

// Export the circle's ID, center coordinates and radius.

}

visitRectangle(d: Rectangle) {

// Export the rectangle's ID, left-top coordinates, width and height.

}

}

// The client code can run visitor operations over any set of

// elements without figuring out their concrete classes. The

// 'accept' operation directs a call to the appropriate operation

// in the visitor object.

const allShapes = [new Dot(), new Circle(), new Rectangle()];

const exportVisitor = new JSONExportVisitor();

allShapes.forEach(shape => shape.accept(exportVisitor));

Concrete visitors implement several versions of the same algorithm, which can work with all concrete element classes.

4.3.3 When to apply, pros and cons

- when you need to perform an operation on all elements of a complex object structure (for example, an object tree). The Visitor pattern allows you to execute an operation over a set of objects with different classes by having a visitor object implementing several variants of the same operation, which correspond to all target classes

- to clean up the business logic of auxiliary behaviors. The pattern allows you to make the primary classes of your app more focused on their main jobs by extracting all other behaviors into a set of visitor classes

- when a behavior makes sense only in some classes of a class hierarchy, but not in others. You can extract this behavior into a separate visitor class and implement only those visiting methods that accept objects of relevant classes, leaving the rest empty

Pros

- introducing new behavior that can work with objects of different classes without changing these classes (Open/Closed)

- moving multiple versions of the same behavior into the same class (Single Responsibility)

- a visitor object can accumulate some useful information while working with various objects. This might be handy when you want to traverse some complex object structure, such as an object tree, and apply the visitor to each object of this structure

Cons

- you need to update all visitors each time a class gets added to or removed from the element hierarchy

- visitors might lack the necessary access to the private fields and methods of the elements that they are supposed to work with

4.4 Command

Command is a behavioral design pattern that turns a request into a stand-alone object that contains all information about the request. This transformation allows you to parameterize methods with different requests, delay or queue a request's execution, and support undoable operations. In other words – it allows to incapsulate actions in objects. The main idea of Command pattern is to provide a way of separating client from receiver.

4.4.1 Command real-life example

Remote control example – we've got on and off buttons, client configures each of these buttons for particular commands. At the same time buttons are not aware of which command are they assigned to. Another example is a friendly waiter taking your order, writing it down on a piece of paper. Then he goes to the kitchen and sticks the order on the wall. After a while, the order gets to the chef, who reads it and cooks the meal accordingly. The cook places the meal on a tray along with the order. The waiter discovers the tray, checks the order to make sure everything is as you wanted it, and brings everything to your table.

4.4.2 Command structure

Good software design is often based on the principle of separation of concerns, which usually results in breaking an app into layers. The most common example: a layer for the graphical user interface and another layer for the business logic. The GUI layer is responsible for rendering a beautiful picture on the screen, capturing any input and showing results of what the user and the app are doing. However, when it comes to doing something important, like calculating the trajectory of the moon or composing an annual report, the GUI layer delegates the work to the underlying layer of business logic. In the code it might look like this: a GUI object calls a method of a business logic object, passing it some arguments. This process is usually described as one object sending another a request.

The Command pattern suggests that GUI objects should not send these requests directly. Instead, you should extract all the request details, such as the object being called, the name of the method and the list of arguments into a separate command class with a single method that triggers this request.

Command objects serve as links between various GUI and business logic objects. From now on, the GUI object does not need to know what business logic object will receive the request and how it will be processed. The GUI object just triggers the command, which handles all the details.

The next step is make your commands to implement the same interface. Usually it has just a single execution method that takes no parameters. This interface lets you use various commands with the same request sender, without coupling it to concrete classes of commands. As a bonus, now you can switch command objects linked to the sender, effectively changing the sender's behavior at runtime.

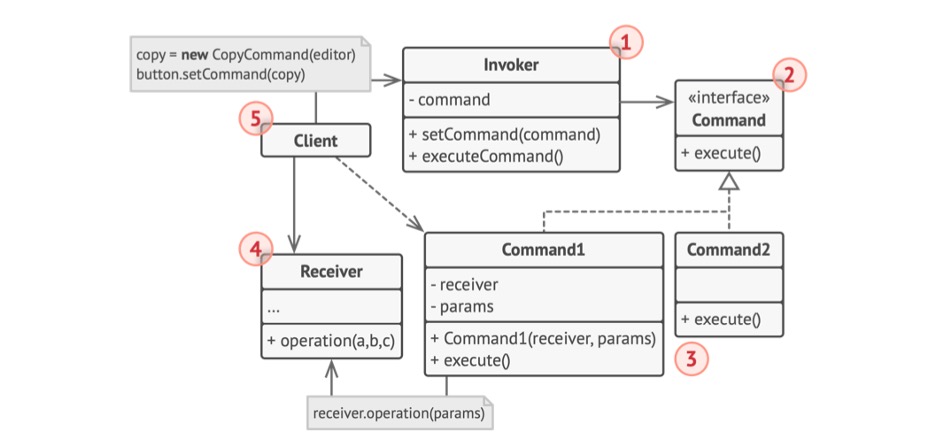

Figure 4.4 - Command

- The

Senderclass (aka invoker) is responsible for initiating requests. This class must have a field for storing a reference to a command object. The sender triggers that command instead of sending the request directly to the receiver. Note that the sender is not responsible for creating the command object. Usually, it gets a pre-created command from the client via the constructor. - The

Commandinterface usually declares just a single method for executing the command. ConcreteCommands implement various kinds of requests. A concrete command is not supposed to perform the work on its own, but rather to pass the call to one of the business logic objects. However, to simplify the code, these classes can be merged.- Parameters required to execute a method on a receiving object can be declared as fields in the concrete command. You can make command objects immutable by only allowing the initialization of these fields via the constructor

- The

Receiverclass contains some business logic. Almost any object may act as a receiver. Most commands only handle the details of how a request is passed to the receiver, while the receiver itself does the actual work. - The Client creates and configures concrete command objects. The client must pass all the request parameters, including a receiver instance, into the command's constructor. After that, the resulting command may be associated with one or multiple senders.

4.4.3 Command example

In this example the Command pattern handles command execution history, allows to cancel them if necessary. Commands, altering the editor state (e.g. paste command), save a copy of editor state before execution.

abstract class Command {

protected app: Application;

protected editor: Editor;

protected backup: string;

constructor (app: Application, editor: Editor) {

this.app = app;

this.editor = editor;

}

saveBackup() {

this.backup = this.editor.text;

}

undo() {

this.editor.text = this.backup;

}

abstract execute();

}

Copies of executed commands are placed into command history, where they can be accessed for cancelling. Classes of UI, command history and others don't depend on concrete commands, since they work via common interface with them. Thus, new commands can be added to application without changing existing code.

class CopyCommand extends Command {

execute() {

this.app.clipboard = this.editor.getSelection();

}

}

class PasteCommand extends Command {

execute() {

this.saveBackup();

this.editor.replaceSelection(this.app.clipboard);

}

}

class CommandHistory {

private history: Command[];

push(c: Command) { this.history.push(c); }

pop(): Command { return this.history[this.history.length -1]; }

}

class Editor {

text: string;

getSelection() { return 'some selection'; }

replaceSelection(clipboard) { return `some ${clipboard} selection`; }

}

The application class sets up object relations. It acts as a sender: when something needs to be done, it creates a command object and executes it.

class Application {

clipboard: string;

editor: Editor;

activeEditor: Editor;

history: CommandHistory;

bindComands() {

shortcuts.onkeypress('Ctrl+C', () => {

return this.executeCommand(new CopyCommand(this, this.editor));

});

shortcuts.onkeypress('Ctrl+V', () => {

return this.executeCommand(new PasteCommand(this, this.editor));

});

}

executeCommand(command: Command) {

this.history.push(command);

command.execute();

}

undo() {

const command = this.history.pop();

command.undo();

}

}

Take the most recent command from the history and run its undo method. Note that we don't know the class of that command. But we don't have to, since the command knows how to undo its own action.

4.4.4 When to apply, pros and cons

- when you want to parametrize objects with operations. The Command pattern can turn a specific method call into a stand-alone object. This change opens up a lot of interesting uses: you can pass commands as method arguments, store them inside other objects, switch linked commands at runtime, etc. Here's an example: you're developing a GUI component such as a context menu, and you want your users to be able to configure menu items that trigger operations when an end user clicks an item

- when you want to queue operations, schedule their execution, or execute them remotely. As with any other object, a command can be serialized, which means converting it to a string that can be easily written to a file or a database. Later, the string can be restored as the initial command object. Thus, you can delay and schedule command execution. But there's even more! In the same way, you can queue, log or send commands over the network

- when you want to implement reversible operations. Although there are many ways to implement undo/redo, the Command pattern is perhaps the most popular of all. To be able to revert operations, you need to implement the history of performed operations. The command history is a stack that contains all executed command objects along with related backups of the application's state. This method has two drawbacks. First, it isn't that easy to save an application's state because some of it can be private. This problem can be mitigated with the Memento pattern. Second, the state backups may consume quite a lot of RAM. Therefore, sometimes you can resort to an alternative implementation: instead of restoring the past state, the command performs the inverse operation. The reverse operation also has a price: it may turn out to be hard or even impossible to implement.

Pros

- decoupling classes that invoke operations from classes that perform these operations (Single Responsibility)

- introducing new commands into the app without breaking existing client code (Open/Closed)

- implementing undo/redo

- implementing deferred execution of operations

- assembling a set of simple commands into a complex one

Cons

- the code may become more complicated since you're introducing a whole new layer between senders and receivers