2. Creational Design Patterns

Creational patterns as we have already mentioned, provide various object creation mechanisms. We are going to cover three of them: abstract factory, singleton and builder.

2.1 Abstract Factory

The Abstract Factory or in simple words – factory of factories.

It provides you an interface for creating objects for each class of the product family. As long as your code creates objects via this interface, you don't have to worry about creating the wrong variant of a product which doesn't match the products already created by your app.

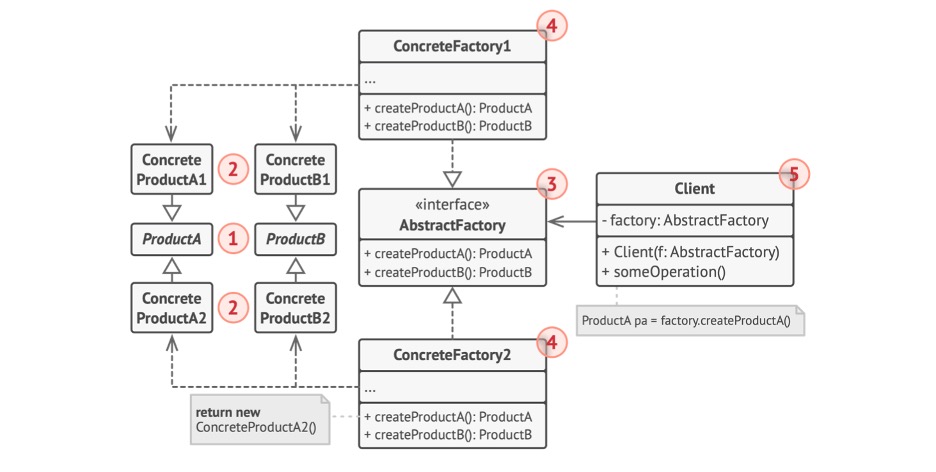

2.1.1 Abstract Factory Structure

Figure 2.1 - Abstract Factory

- Abstract Products declare interfaces for a set of distinct but related products which make up a product family as chair or sofa.

- Concrete Products are various implementations of abstract products, grouped by variants. In this case we implement each abstract product (chair or sofa) in all given variants (Victorian or Modern).

- The Abstract Factory interface declares a set of methods for creating each of the abstract products.

- Concrete Factories implement creation methods of the abstract factory. Each concrete factory creates only those product variants, that corresponds to a specific variant of products.

- Signatures of concrete factories' creation methods must return corresponding abstract products. In this case the client code that uses a factory doesn't get coupled to the specific variant of the product. The Client can work with any concrete factory/product variant, as long as it communicates with their objects via abstract interfaces.

2.1.2 Abstract Factory Example

Here we have 2 kinds of products: door and door fitting master for each type of doors.

interface Door {

getDescription();

}

class WoodenDoor implements Door {

public getDescription() {

return 'I am a wooden door';

}

}

class IronDoor implements Door {

public getDescription() {

return 'I am a iron door';

}

}

interface DoorFittingExpert {

getDescription();

}

class Welder implements DoorFittingExpert {

public getDescription() {

return 'I can only fit iron doors';

}

}

class Carpenter implements DoorFittingExpert {

public getDescription() {

return 'I can only fit wooden doors';

}

}

We declare abstract and concrete products.

Next, our abstract factory that would allow us to create a family of related objects:

- wooden door and a carpenter from wooden door factory

- iron door and a welder from iron door factory

As you can see, the wooden doors' factory contains carpenter's creation and a wooden door, and iron doors' factory contains an iron door and a welder

interface DoorFactory {

makeDoor(): Door;

makeFittingExpert(): DoorFittingExpert;

}

class WoodenDoorFactory implements DoorFactory {

public makeDoor(): Door {

return new WoodenDoor();

}

public makeFittingExpert(): DoorFittingExpert {

return new Carpenter();

}

}

class IronDoorFactory implements DoorFactory {

public makeDoor(): Door {

return new IronDoor();

}

public makeFittingExpert(): DoorFittingExpert {

return new Welder();

}

}

In this case we make sure, that a client who would use a door factory will get a proper specialist for each of the created doors.

2.1.3 When to Apply, Pros and Cons

We should get benefits from usage of the Abstract Factory while working with various families of related products. In this case we are removing the dependency on concrete classes of these products and allowing future extensibility.

The abstract factory encapsulates the details of object creation. But client code can still work with all types of created objects, since their interface is initially defined.

Pros

- ensures compatibility of products

- gets rid of coupling

- extracts the product creation code into one place. (Single responsibility)

- introducing new variants without breaking existing code. (Open/Closed)

Cons

- code becomes more complicated after introducing lots of new interfaces

- after extending abstract factory interface all concrete factories will need to be updated to implement it

2.2 Singleton

Singleton is a creational pattern, which means, that the class has only one instance, and it is accessible from any part of application.

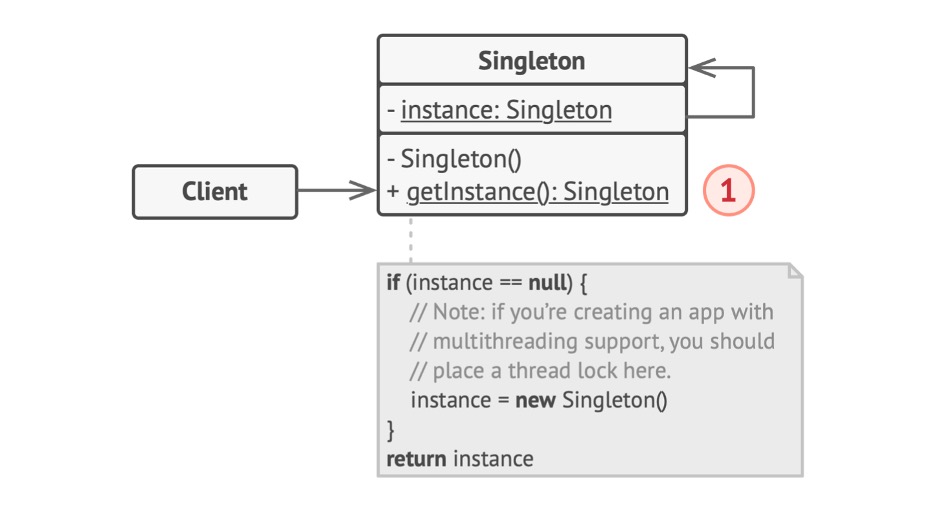

2.2.1 Singleton Structure

Figure 2.2 - Singleton

Singleton defines static method getInstance(), which returns the only instance of its class. The constructor of singleton should be hidden from client code. Calling the getInstance() method should be the only way of getting the Singleton object.

In other words, the Singleton pattern disables all other means of creating objects of a class except for the special creation method. This method either creates a new object or returns an existing one if it has already been created.

Singleton solves two tasks at a time, which violates the single responsibility principle.

- guarantees the existence of single instance of class. It is often useful for accessing common resource, e.g., a database

- provide a global access point to that instance

2.2.2 Singleton Example

All implementations of the Singleton in general do the same – they make default constructor private and create public static method, which controls the lifecycle of singleton object. Under the hood, this method calls the private constructor to create an object and saves it in a static field. All following calls to this method return the saved object.

class President {

private static president: President;

private constructor() {}

public static getInstance(): President {

if (!President.president) {

President.president = new President();

}

return President.president;

}

}

const president1 = President.getInstance();

const president2 = President.getInstance();

president1 === president2 // true

The President is an excellent example of the Singleton pattern. This class doesn't have a public constructor, so the only way to get its instance – is call getInstance() method. This method saves the first created object and will return it in further calls.

2.2.3 When to Apply, Pros and Cons

- if a class in your program should have just a single instance available to all clients; for example, a single database object shared by different parts of the program

- if you need stricter control over global variables

Pros

- you can be sure that a class has only a single instance

- you gain a global access point to that instance

- the singleton object is initialized only when it's requested for the first time

Cons

- violates the Single Responsibility Principle

- pattern can hide bad design

- requires special handling in a multithreaded environment

- you will need to think of a creative way to mock the singleton

2.3 Builder

Builder is a creational design pattern that lets you construct complex objects step by step. The pattern allows you to produce different types and representations of an object using the same construction code. In other words: Builder pattern allows creating different parts of object, avoiding overload of constructor. Builder pattern can be used, when object should be built with several parts, or if objects creation takes lots of steps and each of these steps should be configurable.

Think of it as dividing an object creation into several steps with different parameters.

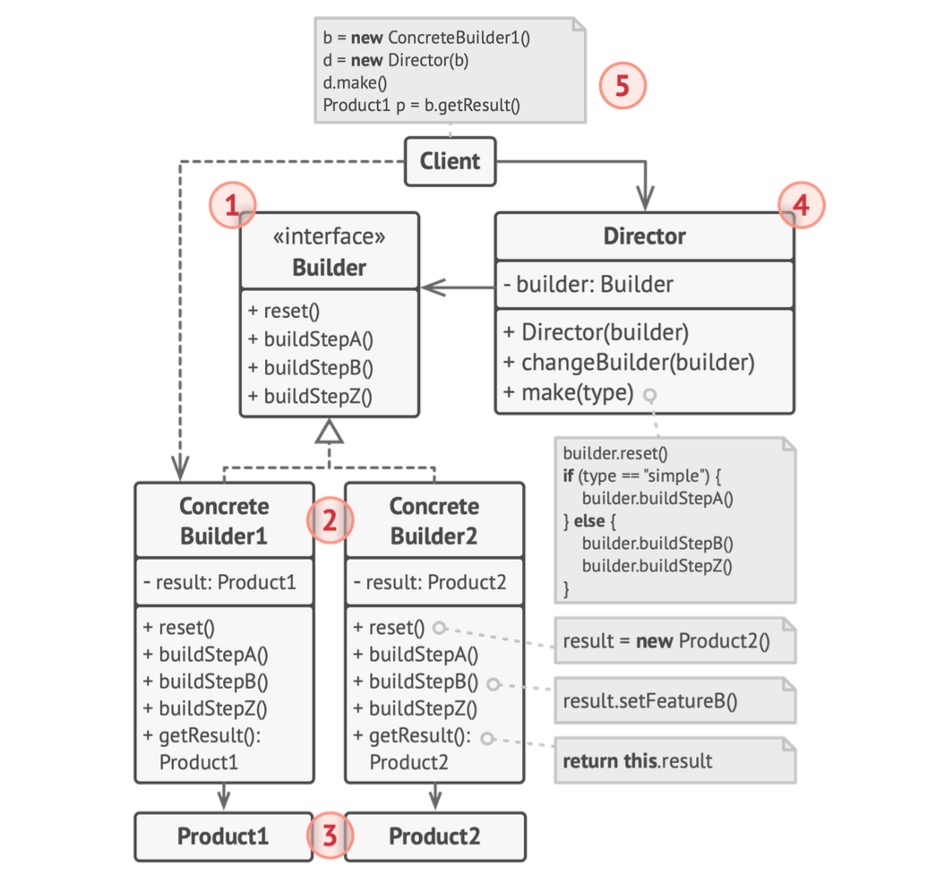

2.3.1 Builder Structure

Imagine a complex object that requires step-by-step initialization of many fields and nested objects. Such initialization code is usually buried inside a huge constructor with lots of parameters. Often most of the parameters will be unused, making the constructor calls ugly.

The Builder pattern suggests you extract the object construction code out of its own class and move it to separate objects called builders. The pattern organizes object construction into a set of steps. To create an object, you execute a series of these steps on a builder object. The important part is that you do not need to call all the steps at a time. You can call only those steps that are necessary for producing a particular configuration of an object.

You can go further and extract a series of calls to the builder steps to construct a product into a separate class called director. The director class defines the order in which to execute the building steps, while the builder provides the implementation for those steps.

Having a director class in your program is not necessary. You can always call the building steps in a specific order directly from the client code.

Figure 2.3 - Builder

- The Builder interface declares product construction steps that are common to all types of builders.

- Concrete Builders provide different implementations of the construction steps. Concrete builders may produce products that do not follow the common interface.

- Products are resulting objects. Products constructed by different builders do not have to belong to the same class hierarchy or interface.

- The Director class defines the order in which to call construction steps, so you can create and reuse specific configurations of products.

- The Client must associate one of the builder objects with the director. Usually, it is done just once, via parameters of the director's constructor. Then the director uses that builder object for all further construction. However, there is an alternative approach when the client passes the builder object to the production method of the director. In this case, you can use a different builder each time you produce something with the director.

2.3.2 Builder Example

This example of the Builder pattern illustrates how you can reuse the same object construction code when building diverse types of products, such as cars, and create the corresponding manuals for them.

class Car {}

interface Builder {

reset();

setSeats(n: Number);

setEngine(n: String);

setTripComputer(n: Boolean);

setGPS(n: Boolean);

}

class CarBuilder implements Builder {

private car: Car;

constructor() {

this.reset();

}

reset() { this.car = new Car(); }

setSeats() {}

setEngine() {}

setTripComputer() {}

setGPS() {}

getProduct(): Car {

const product = this.car;

this.reset();

return product;

}

}

A car is a complex object that can be constructed in a hundred diverse ways. Instead of bloating the Car class with a huge constructor, we extract the car assembly code into a separate car builder class. This class has a set of methods for configuring various parts of a car.

class Director {

private builder: Builder;

setBuilder(b: Builder) {

this.builder = b;

}

makeSportCar(b: Builder = this.builder) {

b.reset();

b.setSeats(2);

b.setEngine('V12');

b.setTripComputer(true);

b.setGPS(true);

}

}

const director = new Director();

const builder = new CarBuilder();

director.makeSportCar(builder);

If the client code needs to assemble a special, fine-tuned model of a car, it can work with the builder directly. On the other hand, the client can delegate the assembly to the Director class, which knows how to use a builder to construct several of the most popular models of cars.

2.3.3 When to Apply, Pros and Cons

- to get rid of a "telescopic constructor" – the pattern lets you build objects step by step, using only those steps that you really need. After implementing the pattern, you do not have to cram dozens of parameters into your constructors anymore

- to construct complex objects – a builder does not expose the unfinished product while running construction steps. This prevents the client code from fetching an incomplete result

Pros

- constructing objects step-by-step, defer construction steps or run steps recursively

- reusing the same construction code when building various representations of products

- isolating complex construction code from the business logic of the product

Cons

- increases complexity of the code since the pattern requires creating multiple new classes

- client will be bound to concrete builder classes, since builders interface does not have a method for fetching the result of the construction