2. SOLID

2.1 Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

info

A class should have one and only one reason to change, meaning that a class should have only one job.

Classes, software components and microservices that have only one responsibility are much easier to explain, understand and implement than the ones that provide a solution for everything. This reduces the number of bugs, improves your development speed, and makes your life as a software developer a lot easier.

Unfortunately, following the single responsibility principle sounds a lot easier than it often is. If you build your software over a longer period and if you need to adapt it to changing requirements, it might seem like the easiest and fastest approach is adding a method or functionality to your existing code instead of writing a new class or component. But that often results in classes with more responsibilities and makes it more and more difficult to maintain the software.

You can avoid these problems by asking simple questions before you make any changes:

- Is this class doing too much? Correct answer: No, it is responsible for only one specific functionality.

- How many sources of new requirements does this class have? Correct answer: Single source or new requirements.

- Who is this class responsible to? Correct answer: It is only responsible to one person or role.

2.1.1 SRP Example

Suppose we have TradeProcessor class, which purpose is to retrieve trade operations from one data source and transfer them to another. TradeProcessor class responsibilities are:

- read each line from the Stream parameter.

- parse fields from each line and store them in an array of

TradeRecordinstances with validation. - iterate over an array of

TradeRecordinstances and save them to the database.

class TradeProcessor {

public process(stream: Stream) {

const connection = new DBConnection(/* */);

const reader: StreamReader = new StreamReader(stream);

const lines: string[] = reader.readLines();

lines.reduce((records: TradeRecord[], line: string) => {

const fields = line.split(',');

if (fields.length !== 2) { /* handle format validation error */}

const [amount, price] = [parseInt(fields[1], 10), parseInt(fields[2], 10)];

if (amount < 0 || price < 0) { /* handle trade validation error */}

return [...records, new TradeRecord(amount, price)];

}, []).forEach((trade: TradeRecord) => {

connection.save(trade);

})

connection.close()

}

}

SRP states that class should have only one reason to change. However, the reality of TradeProcessor is that it will change under the following circumstances:

- You need to change the data source from the stream to the REST API.

- The data format needs to be changed.

- Validation rules have changed.

- When the procedure for saving data to the database changes, for example, instead of mapping incoming parameters to a database table, we will save them in several tables with foreign keys.

Now you need to ask "Who is to blame for the changes?". Having answered it, you will divide the requirements into three groups of responsibilities.

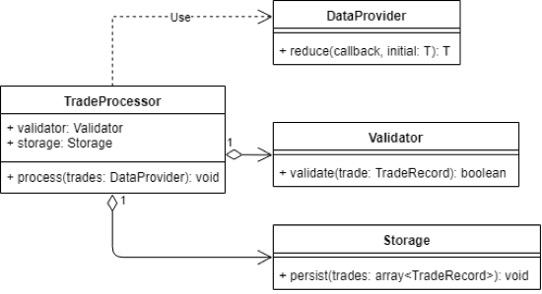

What to do next? Separate the interfaces and as a result make the class follow SRP. So, the first step in refactoring TradeProcessor is to create interfaces that will be used to perform three high-level tasks: reading, processing and storing trade data. In accordance with the SRP, three main responsibilities will be carried out by three different classes.

Figure 2.1 - SRP

So, now the class TradeProcessor is not engaged in the process of reading, parsing, validating and saving trade operations to the database. It is simulating the process of transferring trade data from one format to another. This is its only responsibility and the only reason it can be changed. If the process itself changes, TradeProcessor class will also be changed. If new requirements come for specific parts of the process, they will be introduced into the appropriate classes. In this case there is no need to change TradeProcessor class.

class TradeProcessor {

constructor(private validator: Validator, private storage: Storage) {}

public process(trades: DataProvider) {

const validTrades = trades.reduce((validTrades: TradeRecord[], trade: TradeRecord) => {

if (!this.validator.isValid(trade)) { /* handle invalid data */}

return [...validTrades, trade];

}, [])

this.storage.persist(validTrades);

}

}

You may ask: "What if we already have clients who use TradeProcessor in its previous implementation?" This is a valid question, and ideally you should already have an interface or abstract processor class allocated. We just add a new processor implementation in the form of an adapter composing the new version and adjusting it to the old interface.

If we do not have such abstraction, then we can implement the adapter directly in the current processor implementation, declare it deprecated and remove it in the next version of the application/library.

2.1.2 SRP Summary

When to use?

- Your module is constantly changing and the requirements for changes come from different roles in your project.

- The actions in the module do not correlate with each other.

- The logic in the module is too complex to understand and / or test.

How to apply?

- Combine things that change for one reason. Separate things that change for different reasons.

- Isolate changes, separate the component parts of the module logically.

- Reduce dependencies.

- Apply the principle only when it matters. Do not introduce extra dependencies.

2.2 Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

info

Objects or entities should be open for extension but closed for modification.

Based on the definition above modules have two main characteristics:

- They are open to expansion. It means that the behavior of the module can be extended. When the requirements for the application change, we add new behavior to the module to meet the changed requirements.

- They are closed for modification. It means that extending a module's behavior does not involve changes to the source code of the module.

In other words, we should be able to change the behavior of the module without changing the module itself. How to achieve that?

2.2.1 OCP Example

Let us go back to the TradeProcessor example. When we removed data retrieval, parsing and saving from TradeProcessor class and created separate class for each type of responsibility, we made TradeProcessor class to conform to OCP. If the requirements change, we can get completely different functionality without changing the TradeProcessor itself.

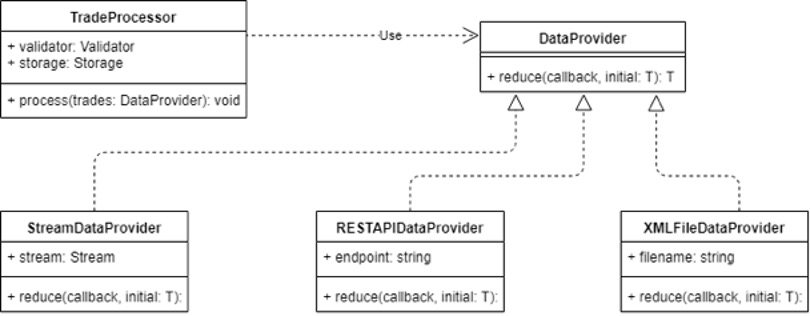

Suppose at some point we were given requirement to support multiple data sources at the same time (stream, REST API and XML file). It is not a problem for us. We can use polymorphic DataProvider in TradeProcessor. As you can see on the diagram below, we have created classes for every data source: StreamDataProvider, RESTAPIDataProvider and XMLFileDataProvider. All of them are inherited from base DataProvider class and override reduce() method. So, in the future, whenever we need to receive data from some new sources, we will do exactly the same thing. Therefore, OCP is not violated. We are closed for modifications (no need to change DataProvider class) and at the same time we are open for expansion.

Figure 2.2 - OCP

2.2.2 Single Choice Principle

Suppose we have a hierarchy of classes designed to import data from files of different formats. We also have a factory method that creates the required Importer depending on the file extension.

Does the implementation of such a factory comply with the OCP? Or do we need to introduce an ImporterFactory interface and factory hierarchy to comply with this principle?

The factory method by itself already hides the way to get the desired Importer from its customers and an additional level of indirection is not needed here.

class ImporterFactory {

public static create(fileName: string): Importer {

switch(getExtension(fileName)) {

case 'json':

return new JsonImporter();

case 'xls':

case 'xlsx':

return new XlsImporter();

default:

throw new Error('Extension is not supported')

}

}

}

Here is what Bertrand Meyer writes about this:

"It is necessary to admit the possibility that the list of variants, given and known at some stage of program development, may subsequently be changed by adding or removing variants. To ensure that this approach to the software development process is implemented, you need to find a way to protect the program structure from the impact of such changes. Hence, follows the principle of Single Choice."

info

In other words: whenever a software system needs to support multiple alternatives, only one module of the system should know the complete list.

2.2.3 OCP Summary

So, the goal of OCP is to minimize changes to existing classes when new functionality is added. It is achieved by adding extension points (not just inheritance) that allow us to take advantage of powerful tools like composition, aggregation, and polymorphism.

2.3 Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

info

Let Q(x) be a property provable about objects x of type T. Then Q(y) should be true for objects y of type S where S is a subtype of T.

To be honest, such a scientific definition might be necessary, but it does not help a lot in our daily work as software developers. So, what does it mean for our code?

The principle defines that objects of a superclass should be replaceable with objects of its subclasses without breaking the application. That requires the objects of your subclasses to behave in the same way as the objects of your superclass. Clients can reliably use any type or subtype, always expecting consistent behavior or, in other words, that the contract will be kept. A simple formulation of the principle is as follows: it should be possible to substitute any subtype for base type.

There are several "rules" that must be followed for LSP compliance: contract rules and variance rules.

2.3.1 Contract Rules

1. Preconditions cannot be strengthened in a subtype

Preconditions are defined as all the conditions necessary for a method to run reliably and without fault. If subclass is replaced with superclass and preconditions are tightened for existing methods, then existing functionality will break.

Suppose we have a class for calculating shipping price ShippingCalculator. This class has calculate() method defined, which takes two arguments: size and weight and calculates delivery price. The calculate() method will not work properly if weight or size provided are less or equal zero. These are preconditions.

Suppose at some point we are given new requirements for shipping service: we need to support worldwide delivery that should be done only if weight and size of product we want to deliver are less than 10. We create class WorldWideShipping that extends ShippingCalculator class and override calculate() method based on new requirements. Now WorldWideShipping does not fulfill ShippingCalculator expectations, because it works only with size and weight less than 10. As a result, WorldWideShipping strengthens preconditions and violates the Liskov substitution principle. All clients should now be aware of the new type and treat it as a special case.

class ShippingCalculator {

public calculate(weight: number, size: number, destination: USADestination) {

if (weight <= 0 || size <= 0) {

throw new Error('Weight and size should be greater than 0')

}

const shippingPrice = weight * size;

return shippingPrice;

}

}

class WorldWideShipping extends ShippingCalculator {

// correct destination type passed: Destination

public calculate(weight: number, size: number, destination: Destination) {

// preconditions are strengthened

if (weight < 10 && size < 10) {

throw new Error('No international shipping for you')

}

return super.calculate(weight, size, destination);

}

}

2. Postconditions cannot be weakened in a subtype

Postconditions check whether an object is being left in a valid state before a method is returned. The reason you cannot weaken postconditions is because existing clients might break when a new subclass is introduced.

Let us get back to ShippingCalculator.calculate() method. The postcondition is the rule that the delivery cost is always more than 0. Suppose our customers decided to bring in free delivery for products which size and weight are less than 1. We create class FreeShipping and override calculate() method based on new requirements. In this case, we weakened postconditions compared to the original ones. We broke the original logic which assumed that the shippingPrice is always a positive number. As a result, clients who are sure in original postconditions and who have previously worked with the base class, may break when switching to the subclass. Moreover, it will also be required for them to check which instance of the calculator they are working with to handle new requirements.

class FreeShipping extends ShippingCalculator {

// incorrect destination type passed: should be Destination

public calculate(weight: number, size: number, destination: TexasDestination) {

if (weight <= 0 || size <= 0) {

throw new Error('Weight and size should be greater than 0')

}

// postconditions are weakened

const shippingPrice = (weight < 1 && size < 1)

? 0

: super.calculate(weight, size, destination);

return shippingPrice;

}

}

2.3.2 Variance Rules

1. There must be covariance of the return types in the subtype.

Covariance is when function return values can be changed to subtypes, moving down the hierarchy. Let us have a look at the example below.

Suppose we have a base Product class defined with getShippingProvider() method which returns an instance of ShippingCalculator class. We want to introduce a new product phone, that is why we create Phone class and extend it from base Product class. Phones can be delivered worldwide. Therefore, getShippingProvider() should return an instance of WorldWideShipping class. Covariance of return types is kept: getShippingProvider() returns an instance of WorldWideShipping class, which is subtype of ShippingCalculator (moving down to hierarchy).

class Product {

public getShippingProvider() : ShippingCalculator {

return new ShippingCalculator();

}

}

class Phone extends Product {

// WorldWideShipping is subtype of ShippingCalculator

public getShippingProvider() : WorldWideShipping {

return new WorldWideShipping();

}

}

Example of violating the covariance rule of return types in subtype is given below. As you can see, we are moving up the hierarchy of classes.

class Product {

public getShippingProvider() : WorldWideShipping {

return new WorldWideShipping();

}

}

class Phone extends Product {

public getShippingProvider() : ShippingCalculator {

return new ShippingCalculator();

}

}

2. There must be contravariance of the method arguments in the subtype.

Contravariance is when function arguments can be changed to supertypes, moving up the hierarchy. Let us have a look at the example below.

Suppose at some point we decided to deliver products only to the USA and free shipping is possible only to Texas. We extend calculate() method and pass destination needed to it. Contravariance of function arguments is kept in WorldWideShipping class, but not in FreeShipping class. Destination should be an instance of Destination class in FreeShipping.calculate() method.

class Destination {}

class USADestination extends Destination {}

class TexasDestination extends USADestination {}

class ShippingCalculator {

public calculate(weight: number, size: number, destination: USADestination) {

// calculate

}

}

class WorldWideShipping extends ShippingCalculator {

// correct destination type passed: Destination

public calculate(weight: number, size: number, destination: Destination) {

// calculate

}

}

class FreeShipping extends ShippingCalculator {

// incorrect destination type passed: should be Destination

public calculate(weight: number, size: number, destination: TexasDestination) {

// calculate

}

}

3. Invariants must be maintained.

A data invariant is a state that remains true for the entire lifetime of an object. Data invariants refer to the expected internal state of an object. Whenever a new subclass is created, it must continue to honor all the data invariants that were part of the base class. The violation of this principle is easy to introduce because subclasses have a lot of freedom to introduce new ways of changing previously private data.

A list of users with unique emails can be an example of a data invariant. Let us have a look at Users.add() method. By adding a simple guard condition to the method, we prevented adding an invalid value and preserved the data invariant. In NotUniqueUsers.add() method we violate the parent class invariants, since we give the opportunity to add non-unique values to the collection of users. Data invariants must be persisted throughout the hierarchy of classes. Every class in the chain of inheritance must fulfill the invariants of all its heirs, otherwise no one can guarantee the correctness of the behavior.

class User {

constructor(private email: string) {}

hasSameEmail(other: User) : boolean {

return other.email === this.email;

}

}

class Users {

private users: User[] = [];

public add(user: User) : boolean {

if (this.users.some(user.hasSameEmail.bind(user))) {

return false;

}

this.users.push(user);

return true;

}

}

class NotUniqueUsers extends Users {

private collection: User[] = [];

public add(user: User) : boolean {

this.collection.push(user);

return true;

}

}

2.3.3 LSP Summary

In case of not following LSP:

- Inheritance hierarchies will lead to confusion. So, passing the subclass instance instead of base class into the method will result in a weird behavior of the existing code.

- Unit tests for base class will never pass for subclasses.

2.4 Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

info

A client should never be forced to implement an interface that it does not use, or clients should not be forced to depend on methods that they do not use.

The goal of this principle is to reduce the side effects of using larger interfaces by breaking application interfaces into smaller ones. It is like the Single Responsibility Principle, where each class or interface serves a single purpose.

Precise application design and correct abstraction is the key behind the Interface Segregation Principle. Though it will take more time and effort in the design phase of an application and might increase the code complexity, in the end, we get a flexible code.

2.4.1 ISP Example

Let us have a look at the example below. We have Staff interface and class Lecturer that implements Staff interface. Thus, it does not violate the principle. For simplicity, let us ignore the actual business implementation of these methods.

interface Staff {

name: string,

salary: number,

adjustSalary(): number,

}

class Lecturer implements Staff {

constructor(public name:string, public salary:number) {}

adjustSalary() { return this.salary * 0.9 }

}

Now, as we move ahead in time, and more features come in, there is a need to add management staff, so we created Administrator class. Everything looks good so far. But what if we need to extend Lecturer and Administrator classes behavior? Let us say that we want to add giveLecture() method to Lecturer class and arrangeMeeting() to Administrator. In this case we need to extend Staff interface with those methods.

interface Staff {

name: string,

salary: number,

adjustSalary(): number,

giveLecture():void,

arrangeMeeting(): void

}

class Lecturer implements Staff {

constructor(public name: string, public salary: number) {}

adjustSalary() { return this.salary * 0.9 }

giveLecture() {}

arrangeMeeting() {}

}

class Administrator implements Staff {

constructor(public name: string, public salary: number) {}

adjustSalary() { return this.salary * 0.75 }

arrangeMeeting() { }

giveLecture() {}

}

Now, since the Staff interface has changed and more methods were added, all the implementing classes now must implement the new methods. The problem is, implementing them is unwanted and could lead to many side effects. Here, the Administrator implementation class must implement the giveLecture() method without any actual need for this. And so, the principle is violated.

Let us break up the interfaces and apply the Interface Segregation Principle. As you can see, we have created two more interfaces AcademicStaff and ManagerStaff that extend the base Staff interface. Each of the new interfaces contain only those methods that they need. Therefore, Lecturer class now implements AcademicStaff and Administrator class AcademicStaff interface.

interface Staff {

name: string,

salary: number,

adjustSalary(): number,

}

interface AcademicStaff extends Staff {

giveLecture(): void,

}

interface ManagerStaff extends Staff {

arrangeMeeting(): void,

}

class Lecturer implements AcademicStaff {

constructor(public name: string, public salary: number) {}

adjustSalary() { return this.salary * 0.9 }

giveLecture() {}

}

class Administrator implements ManagerStaff {

constructor(public name: string, public salary: number) {}

adjustSalary() { return this.salary * 0.75 }

arrangeMeeting() { }

}

2.4.2 ISP Summary

As you can see fat interfaces lead to inadvertent coupling between classes, and you should avoid them. When designing interfaces, you should always ask yourself the question "Do really need all the methods on this interface I'm using? If not, how can I break them into smaller interfaces?". Treat interface segregation with certain pragmatism and use common sense.

2.5 Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

info

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions. Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

The general idea of this principle is as simple as it is important: High-level modules, which provide complex logic, should be easily reusable and unaffected by changes in low-level modules, which provide utility features. To achieve that, you need to introduce an abstraction that decouples the high-level and low-level modules from each other. The design principle does not just change the direction of the dependency, as you might have expected when you read its name for the first time. It splits the dependency between the high-level and low-level modules by introducing an abstraction between them. So, in the end, you get two dependencies: the high-level module depends on the abstraction, and the low-level depends on the same abstraction.

2.5.1 DIP Example

Let us dive deep into dependency inversion principle by having a look at the example below. Suppose we are working on an application that uses MySQL database. We have UserTransaction class that will be used to query User table in the database. It contains init() method that takes instance of MySQLDatabase class and two base operations: insert() and delete().

interface Database {

insert(entity: object): object

delete(entity: object): object

get(entity: object): object

}

class UserTransaction {

private db;

init(db: MySQLDatabase) { this.db = db }

insert(user: object) { return (!this.db.get(user)) ? this.db.insert(user) : null; }

delete(user: object) { return (!this.db.get(user)) ? this.db.delete(user) : null; }

}

MySQLDatabase is a low-level module, UserTransaction is a high-level one. But based on the definition of the Dependency Inversion Principle, which says to separate abstractions from the implementation, this fragment of code violates it, because the UserTransaction class depends on the MySQLDatabase class.

But what if at some point we decided to replace MySQL to PostgreSQL database, which has a completely different interface compared to MySQL? We would not only need to create PostgreSQLDatabase class, but also update UserTransaction class implementation.

class PostgreSQLDatabase {

insert(entity: object) { return { /* insert using PostgreSQL syntax */ } }

delete(entity: object) { return { /* delete using PostgreSQL syntax */ } }

get(entity: object) { return { /* get using PostgreSQL syntax */ } }

}

There should be low coupling between classes used. UserTransaction class does not have to worry about the database being used. To fix that, we have to create an interface so that the low-level and high-level modules depend on the abstraction (interface).

interface Database {

insert(entity: object): object

delete(entity: object): object

get(entity: object): object

}

class PostgreSQLDatabase implements Database {

insert(entity: object) { return { /* insert using PostgreSQL syntax */ } }

delete(entity: object) { return { /* delete using PostgreSQL syntax */ } }

get(entity: object) { return { /* get using PostgreSQL syntax */ } }

}

class UserTransaction {

private db;

init(db: Database) { this.db = db }

insert(user: object) { return (!this.db.get(user)) ? this.db.insert(user) : null; }

delete(user: object) { return (!this.db.get(user)) ? this.db.delete(user) : null; }

}

Now both modules (low-level and high-level) depend on abstraction. No matter which database is used (either PostgreSQL or MySQL), UserTransaction class depends on Database interface. Therefore, if at some point we decide to roll back to MySQL or introduce a new database, we will not need to change the UserTransaction class. Dependency Inversion principle is not violated, and we can introduce new requirements very quickly without changing all the related modules.

2.5.2 DIP Summary

The Dependency Inversion Principle is the fifth and final design principle that we discussed in this lecture. It introduces an interface abstraction between higher-level and lower-level software components to remove the dependencies between them.

When to allocate an interface from a class?

- Class is an implementation of some strategy and will be used in a polymorphic manner.

- Class is used to work with external environments (files, sockets, configuration, etc.).

When not to allocate a class interface?

- Class is an immutable Value Object or Data Object.

- Class has stable behavior (does not work with the external environment).